- 22 Apr 2016 20:04

#14672946

It is the centenary of the start of the Easter Rising in Ireland on Sunday 24th April. An uprising that triggered an independence movement in Ireland. The barbarism of the English against the Irish people had been going on for many centuries. This is worth reading...

___________________________________________________________________________________________

IF I HAD UNDERSTOOD THE SITUATION A BIT BETTER I SHOULD HAVE PROBABLY JOINED THE ANARCHISTSGeorge Orwell

It is the centenary of the start of the Easter Rising in Ireland on Sunday 24th April. An uprising that triggered an independence movement in Ireland. The barbarism of the English against the Irish people had been going on for many centuries. This is worth reading...

The events of Easter week 1916 would spark the flame of a Nation that was long since slumbering.

After years of fruitless political negotiations by constitutional nationalist parties, Home Rule for Ireland appeared as far away as ever in the spring of 1916.

Unionism was armed and threatening civil war, the British army had threatened mutiny rather than face down the unionists and the rights of the Irish people was the last thing on the mind of a British Government locked in a bloody European war.

At this pivotal point in our history a small group of Republicans stepped forward and took on the British Empire in defence of those rights.

Soldiers of the Irish Volunteers and the Irish Citizen Army, led by Padraig Pearse, determined that they would not permit Britain to ignore Ireland’s claim to independence. Unlike the constitutional nationalists, Pearse and his colleagues did not seek merely Home Rule. They believed that Ireland should be free from British influence and sought the establishment of an Irish Republic.

James Connolly, trade unionist and commander of the Irish Citizen Army went further. He argued for the establishment of a Socialist Republic which enshrined the rights of the working people.

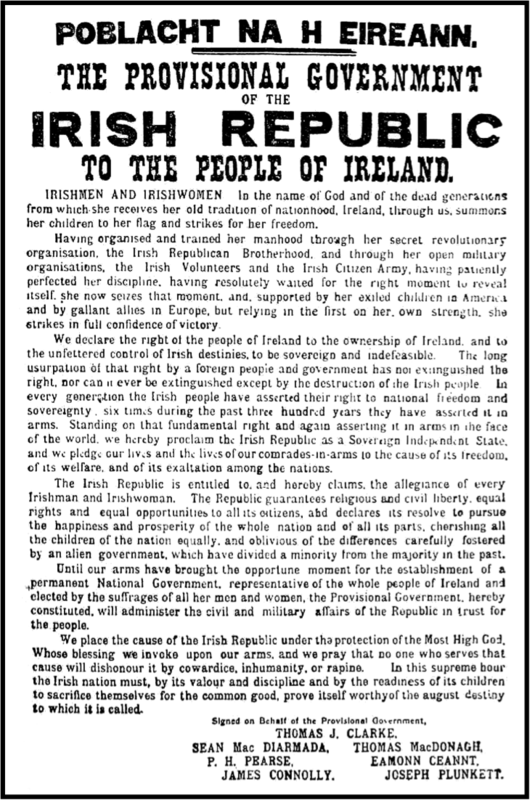

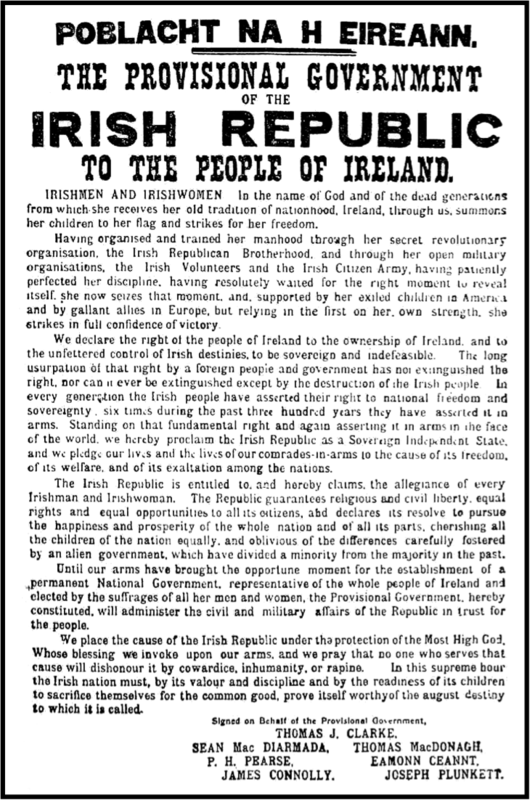

The Proclamation of the Irish Republic spelled out the key principles on which the new Republic would be based. The document was years ahead of it’s time and remains the most important statement of intent in the history of this island.

Pearse, Connolly and the others, decided to act before the end of the Easter holidays and what followed was one of the most dramatic and heroic episodes in Irish history.

At about 11.00 am on Easter Monday the Volunteers, along with the Irish Citizen Army, assembled at various prearranged meeting points in Dublin, and before noon set out to occupy a number of imposing buildings in the inner city area.

The original plan, largely devised by Plunkett, was to seize strategic buildings throughout Dublin in order to cordon off the city and resist the inevitable counter-attack by the British army. If successful, the plan would have left the rebels holding a compact area of central Dublin, roughly bounded by the canals and the circular roads.

The Volunteers' Dublin division had been organized into 4 battalions. A makeshift 5th battalion was put together from parts of the others, with additional troops from the Citizen Army. This was the battalion of the headquarters at the General Post Office, and included the President and Commander-in-Chief, Pearse, the commander of the Dublin division, Connolly, as well as Clarke, Mac Diarmada, Plunkett, and a then-obscure young captain named Michael Collins.

Connolly asked Eamon Bulfin to hoist two flags up on the flag poles on either end of the GPO roof. The tricolour was hoisted at the right corner of Henry Street while a green flag with the inscription 'Irish Republic' was hoisted at the left corner at Princess Street. A short time later, Pearse read the Proclamation of the Republic outside the GPO.

A small team of volunteers attacked the Magazine Fort in the Phoenix Park in an effort to obtain weapons and create a large explosion to signal the start of the rising. Meanwhile the 1st battalion under Commandant Ned Daly seized the Four Courts and areas to the northwest; the 2nd battalion under Thomas MacDonagh established itself at Jacob's Biscuit Factory, south of the city center; in the east Commandant Éamon de Valera commanded the 3rd battalion at Boland's Bakery; and Ceannt's 4th battalion took the workhouse known as the South Dublin Union to the southwest.

Members of the ICA under Michael Mallin and Constance Markievicz also commandeered St. Stephen's Green. An ICA unit under Seán Connolly made a minor assault on Dublin Castle, not knowing that it was defended by only a handful of troops.

After shooting dead a police sentry and taking several casualties themselves from sniper fire, the group occupied the adjacent Dublin City Hall. Seán Connolly was the first Republican casualty of the week, being killed outside Dublin Castle. Other volunteers also occupied 25 Northumberland Road and Clanwilliam House where seven Volunteers held off the British advance for nine hours.

As the week progressed, the fighting in some areas did become intense, characterised by prolonged, fiercely contested street battles. British casualties were highest at Mount Street Bridge. There, newly arrived British troops made successive, tactically inept, frontal attacks on determined and disciplined volunteers occupying several strongly fortified outposts.

The British lost 234 men, dead or wounded while just 5 Republicans died. British soldiers killed 15 unarmed men in North King Street near the Four Courts during intense gun battles there on 28th and 29th April.

The pacifist Francis Sheehy-Skeffington was the best- known civilian victim of the Easter Rising. He was arrested in Dublin on 25th April, taken to Portobello Barracks and shot by firing squad the next morning.

As Eoin MacNeill's countermanding order prevented nearly all areas outside of Dublin from rising, the command of the great majority of Republican Volunteers fell under Connolly. After being badly wounded, Connolly was still able to command by having himself moved around on a bed.

The British commander, Brigadier-General Lowe, worked slowly, unsure of how many he was up against, and with only 1,200 troops in the city at the outset. Lord Wimborne, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, declared martial law and the British forces put their efforts into securing the approaches to Dublin Castle and isolating the Republican headquarters at the GPO.

Their main firepower was provided by the gunboat Helga and field artillery summoned from their garrison at Athlone which they positioned on the north side of the city at Prussia Street, Phibsborough and the Cabra road. These guns shelled large parts of the city throughout the week and burned much of it down. So inaccurate was much of the fire that British units, believing that they were being shelled by Republican guns-of which there were none-returned fire against their own artillery.

Interestingly the Helga's guns had to stop firing as the elevation necessary to fire over the railway bridge meant that her shells were endangering the Vice Regal Lodge in Phoenix Park.

By Wednesday morning the Republicans were outnumbered 20 to one. The British now began to attack in earnest. Their first major action was to destroy Liberty Hall, the headquarters of the Labour Party and of the trade unions, by shellfire from the Helga.

As it happened, the Republicans had anticipated this, and the building was empty. The British gunfire was inaccurate and many other buildings were hit and many civilians killed. The British army also used artillery without consideration for civilian casualties, for example a 9 -pounder gun was fired against a single sniper.

Dublin began to burn, and the Dubliners to starve, for there was no food coming into the city. This was no longer a police action but full-scale war in which no attempt was made to spare the civilians.

Meanwhile, British reinforcements marching in from Kingstown were ambushed by de Valera's men and suffered heavy casualties, but by dint of numbers forced their way through. St Stephen's Green had been cleared of Volunteers, who retreated into the Royal College of Surgeons, and established a strongpoint there.

On Thursday the new British commander in-chief arrived. Since Ireland was under martial law, he held full powers there. This was General John Maxwell. Although he numbered the Countess Markiewicz among his relations, he had no knowledge of the current political mood in Ireland, and, indeed, as events were to prove, did more to undermine British rule in Ireland than all the rebels put together.

He had been ordered by the British Prime Minister, Asquith, to put down the rebellion with all possible speed. And this he did regardless of political consequences.

The reinforcements from England were now in action. Frustrated by experienced and determined Irish Republican Army units (as the Volunteers were now calling themselves), some of these British troops began committing atrocities against the civilian population and a number of civilians were shot dead without challenge.

On Thursday attacks were made on Boland's Mill, the men in the South Dublin Union were forced to give ground, and there was shelling of' the General Post Office, which began to burn from the top down. Connolly was wounded twice. The first wound he hid from his men the second was more serious, for one foot was shattered and he was in great pain. With the aid of morphia he carried on, directing the battle as best he could.

The heaviest fighting occurred at the Republican positions around the Grand Canal, which the British seemed to think they had to take to bring up troops who had landed in Dún Laoghaire port. The Republicans held only a few of the bridges across the canal and the British might have availed themselves of any of the others and isolated the positions.

Due to this failure of intelligence, the Sherwood Foresters regiment were repeatedly caught in a cross-fire trying to cross the canal at Mount Street. Here a mere seventeen volunteers were able to severely disrupt the British advance, killing or wounding 240 men.

The Republican position at the South Dublin Union also inflicted heavy losses on British troops trying to advance towards Dublin Castle. Cathal Brugha, a Republican l officer, distinguished himself in this action and was badly wounded.

Shell fire and shortage of ammunition eventually forced the Republicans to abandon these positions before the end of the week. The defensive position at St Stephen's Green, held by the Citizen Army under Michael Mallin, was made untenable after the British placed snipers and machine guns in the surrounding buildings. As a result, Mallin's men retreated to the Royal College of Surgeons building, where they held out until they received orders to surrender.

On Friday, Connolly ordered the women who had fought so bravely to leave the General Post Office building, which was now cut off and burning. The garrison at the GPO barricaded themselves within the post office and were soon shelled from afar, unable to return effective fire, until they were forced to abandon their headquarters when their position became untenable.

The GPO garrison then hacked through the walls of the neighbouring buildings in order to evacuate the Post Office without coming under fire and took up a new position in Moore Street. A last battle was fought for King's Street, near the Four Courts. It took some 5,000 British soldiers, equipped with armoured cars and artillery, 28 hours to advance about 150 yards against less than 200 Republicans.

It was then that the troops of the South Staffordshire Regiment bayoneted and shot civilians hiding in cellars.

On Saturday April 29 from this new headquarters, after realizing that all that could be achieved was further loss of life, Pearse issued an order for all units to surrender.

The British Army reported casualties of 529 killed or wounded and 9 missing (including RIC). The Irish Republican Army (as it would be known thereafter) recorded 64 killed in action with an unknown number of wounded. Over 250 civilians were killed, many by British shellfire, and several thousand wounded.

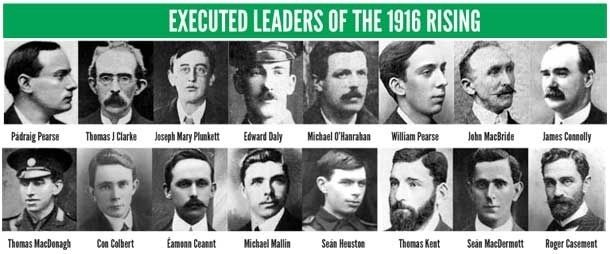

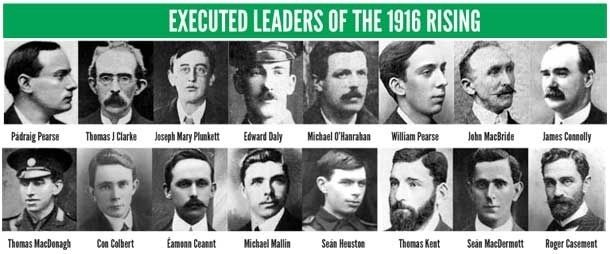

The British wasted no time in executing the leaders of the Rising in an attempt to deter any future opposition.

What the British called "The Sinn Féin Rising" was over, but the new Irish Republican Army had learned valuable lessons, which they would put to good use in later years.

The Irish people, shocked at the brutality of the British army and stunned by the courage of the Republican forces began the debate which would move national sentiment away from constitutional nationalism and toward Republicanism.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

It cannot be underestimated the barbarism of the English against the Irish people that had been going on for many centuries.

During the 16th and 17th Century, the English Monarchy and Parliament attained effective dominion over the island of Ireland through a series of confiscations of Irish Catholic-owned land, and the subsequent colonization of this land by settlers from England and Scotland. These ‘plantations’ were to cause extreme demographic and political changes, led at least in part to the irreparable decline of the Irish language, and effectively amounted to a policy of genocide against the Irish Catholic population.

Many of these plantations were not just tools of colonization; they were also punitive measures that were taken in response to attempted rebellions. Early attempts at small-scale plantations were somewhat unsuccessful, as the dispossessed Irish often took to guerilla raids on the new colonies, resulting in a number of revenge atrocities against the natives and a lack of enthusiasm among would-be English and Scottish settlers for the lands in question. The Munster Plantation of the 1580s was to be the first mass plantation of the country. It was undertaken in response to the Desmond Rebellions. The Crown forces, led by Earl Arthur Grey, used brutal, scorched earth tactics to put down the rebellion of Gerald Fitzgerald, the earl of Desmond, resulting in a serious famine which had killed as many as 30,000 people in just six months in 1582. In all, up to a third of the population of the province may have been killed as a result of the famine which resulted from the English activities in the area, and the province was reduced to a “barren wasteland”. This approach was later advocated by Edmund Spenser in his pamphlet “A View of the Present State of Ireland” as being a suitable way to conquer and subjugate Ireland.

“Out of everye corner of the woode and glynnes they came creepeinge forth upon theire hands, for theire legges could not beare them; they looked Anatomies of death, they spake like ghostes, crying out for their graves…if they found a lott of watercresses or shamrocks theyr they flocked as to a feast for the time…yet sure in all that war, there perished not manye by the sword but all by the extremitie of famine which they themselves had wrought.”- (Edmund Spenser, quoted in Jenkins, 1952; p132)

The process of plantation continued with the Ulster Plantation, which began in 1606. Again, native Irish Catholics were displaced from their lands in response to their participation in the Nine Years War of 1594-1603, and also due to the departure of Irish Catholic nobility from Ulster for Spain, where they had hoped to raise a force capable of mounting a new rebellion against the English Monarch. It is this plantation which has arguably had the most enduring tangible effects, as it was responsible for the creation of the large Protestant and Presbyterian groups which now hold a demographic majority in Northern Ireland.

The process of plantation was completed with the Cromwellian plantation of 1652, which was conducted largely as a result of the Irish support for King Charles I in the English Civil War, and the related Irish Confederate Wars, which were a concerted effort by an Irish Catholic government to reverse the plantation system. In revenge for this, Oliver Cromwell led an army of 12,000 men (mostly hardened veterans of the Civil War) in August 1649 to Dublin. This force immediately marched north towards the walled town of Drogheda, which was besieged, sacked and pillaged with the loss of around 1,000 Irish troops and as many as 3,000 civilians, with many of the survivors being sold into slavery. A week after this, the Cromwellian forces similarly laid waste to the town of Wexford in a calculated act of terror against the Irish Catholic population. Over the course of the next few years, his forces attacked and defeated Catholic armies and garrisons in several different towns and cities throughout the country, ultimately ending the Confederate Wars.

Following the pacification of the Irish and Royalist forces, Cromwell enacted a series of penal laws against Irish Catholics, which included banning Catholics from holding office in the Irish Parliament and which expelled Catholic clergy from the country and made the practice of Catholic Mass illegal. Additionally, Catholics were forbidden from living in towns. Most importantly, major land confiscations were undertaken. Any Catholic landowner who had participated in the Confederate Wars were stripped of their lands and deported to the West Indies as slaves (about 40,000 people in total); other Catholic landowners likewise had their properties seized, although they were allowed to receive lands in the western-most province of the country (which were often much poorer than the lands they had given up) in compensation. This was principally done to control the Catholic landlords, by pinning them between the Atlantic Ocean and the River Shannon. Shortly after this, the percentage of Catholic landowners in the country had dropped from roughly 60% of the population to merely 8%. In addition, it has been estimated that as much as a third of the Irish Catholic population of the time was killed or deported.

IF I HAD UNDERSTOOD THE SITUATION A BIT BETTER I SHOULD HAVE PROBABLY JOINED THE ANARCHISTSGeorge Orwell

- By Pants-of-dog

- By Pants-of-dog - By Rancid

- By Rancid