Jihsan wrote:feihua hanashimashita: Thousands of innocent civilians were killed.

The Japanese government does not even see it that way.

feihua also hanashimashita: They are comfortable with how things worked out.

How can you debate this?

This is implying that Japan had no intentions to protect their Empire, their Interest (whatever it may be)

You are the one who is supposed to debate it, not me.

It is not part of a debate from me.

We have to cut down on some of the noise first......you are using the words "their Interest" and then saying "whatever it may be" acknowledging it is just a catch all for you.

That out of the way, You are saying my words imply Japan had no intentions to protect their Empire.

I have strong doubts my words imply that.

HOWEVER

Yeah......I am in doubt that Japan had strong intentions to protect what was left of their Empire. And I am not convinced at this point that you have paid much attention to what I posted.

Japan had strong intentions to fight to the death. Fighting to the death is not about protecting an Empire.

Japan

as you know itas I know itas the world knows itfrom that waris g o n e.That Empire is gone.That government no longer exists. That Empire you speak of does not exist and has not existed for a very long time.

That government took very little effort in taking account of their own citizens and property during the firebombings. That is why Japan often gets sued by the citizens of Japan regarding World War 2 whereas the same citizens do not attempt to take other countries to account for the damage and deaths created by the firebombings by the USA.

I do not think you are aware of what I am mentioning.

It does not appear you read the following that is still posted above:

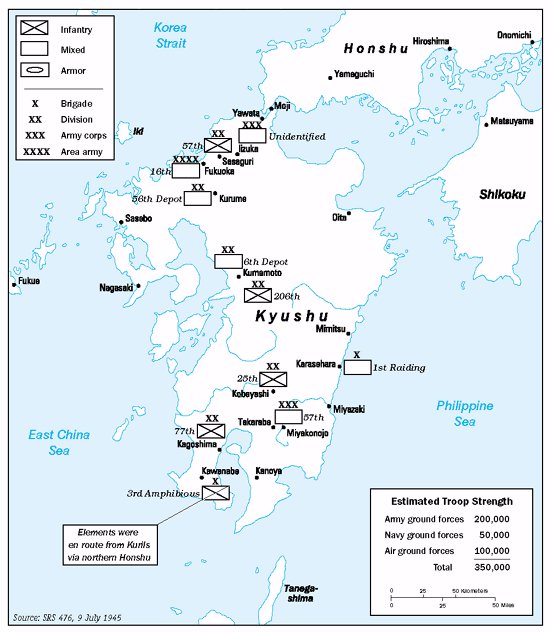

By August, they had 14 divisions and various smaller formations, including three tank brigades, for a total of 900,000 men [on Kyushu].

Although the Japanese were able to raise large numbers of new soldiers, equipping them was more difficult. By August, the Japanese Army had the equivalent of 65 divisions in the homeland but only enough equipment for 40 and only enough ammunition for 30.

The Japanese did not formally decide to stake everything on the outcome of the Battle of Kyūshū, but they concentrated their assets to such a degree that there would be little left in reserve. By one estimate, the forces in Kyūshū had 40% of all the ammunition in the Home Islands.

In addition, the Japanese had organized the Patriotic Citizens Fighting Corps, which included all healthy men aged 15 to 60 and women 17 to 40 for a total of 28 million people, for combat support and, later, combat jobs.Japan is indeed comfortable with how things have worked out. It is a much better country. It is a much safer country. It is a different government. It has a greater amount of respect in the world. It has no need for war. It will not assist other countries in carrying out war.

There is a big effin' reason people live as long as they do in the very place that created the greatest amount of casualties: the stress factor is zilch compared to other countries.The debate is for you to do. I wouldn't advise it. Shrugs. I am nonetheless game for it happening.

I mean, what on Earth are you looking for? You want to talk about vivisections in Fukuoka? I worked at Kyudai where those vivisections took place. I lived next door to what was the POW camp at Hakozaki. Do you know what Hakozaki is famous for? It is famous for being the very location that green tea was introduced to Japan. Was such a cultural landmark protected by the Empire you speak of? It was a pit turned into a POW camp that fed soldiers to the University of Kyushu for doctors to dissect. At that location, I know where a man's liver was removed and served charcoal grilled with soy sauce. That was no early war capture. It involved US forces. What is this Empire you speak of that was protected? It is gone. Records are gone. Even the doctor that performed that vivisection and denied it year after year after year lives to this day in Fukuoka and operates a ob-gyn clinic. This is how we know of these details when these records from the Empire are gone along with the Empire. These are confessions.

Are you actually going to contradict first hand accounts?!?With what?!?In that map of Kurume.....Iizuka......Fukuoka......I know more people than I have ever met in the USA. A great deal more and that is quite a large number considering what I did in the States before moving to Japan. I am speaking of thousands, not hundreds. Tens of thousands.

Not once have I ever come across a local who said "Saa, zannen desu ne. That bomb was not needed because after Okinawa we thought the Red Cross was going to show up."I will show you quite easily how the war was continuing. I can connect you with people from families that feared for their lives greatly not because of invading US forces but because the government was requiring them to join in the fighting. And what choice did they have for they were not going to be shipped out - the war was coming directly to their homes. Look at a satellite map of Kyushu on GoogleEarth. Look at the mountains. Those cannot be crossed except through valleys or the only few and

very few roads that progress towards Fukuoka. The tunnels that are present today were not present then. Perhaps one third of those roads did not exist. The only way to get to Fukuoka was going to be town to town as they exist in the valleys. They were not going to be defended with much ammunition at all. They were going to be defended by citizens simply to slow down the enemy and inflict casualties. Suicide is not about protection. Suicide is to inflict damage.

That is my home. Those are my friends. And hardly anyone moves in Japan. These people can only count two locations as homes they had in their entire lives. These communities have been in place for at least four generations with many exceeding that number. No one was bullshitting me they wished the war to continue. No one has bullshitted me thinking they were going to be excused after the defeat in Okinawa.

GoogleEarth has not yet had the ability to let the cars map the streetview of Japan. Give it some time. I will have no problem showing you bunkers and machine gun nests that exist today, covered up in weeds, near Kurume. I will show you treelines along mountains surrounding the valley of Iizuka that blazed in the summer of '45 to clear the way for the POWs in Keisen to build the bunkers and machine gun nests before they were to be exterminated immediately prior to the landing of the US forces.

There was no war there on the ground but it was expected, and it was prepared and waiting. What do you want? First hand accounts from POWs in Fukuoka who were quite aware the war would be continuing?

That war was Not over in Okinawa. It is foolish to think it was, but you are the one who wants to debate that.

How can I debate

what?

I am not debating a damn thing. Yet, I will entertain one if that is what you want to initiate. And I will repeatedly provide examples of how the claim that Japan was going to end the war without the bombs being dropped and without the invasion of Kyushu as being total nonsense.

It is amazing you cannot accept the evidence already presented. It is not surprising, however.

"Butter is fresh. Margarine is indestructible."

- By Tainari88

- By Tainari88