Local Localist wrote:The average person doesn't know why they believe what they do, they don't have to know, and it's probably best that they don't know, because if they really thought independently, they would most likely not be happy or productive workers.

I would say that the average person is a subscriber. They don't have a point of view. Rather, they subscribe to one. I've seen people evolve their views, but I have also seen people change their minds to just conform to the current zeitgeist.

Local Localist wrote:This does not mean, however, that the proscriptions of the enlightenment were wrong. They were entirely necessary to lift everyone out of feudalism and the mindset that education and wealth should be restricted only to a small elite.

Feudalism wasn't simply about restricting education or wealth to a small elite. Feudalism as barons and knights more or less running government was hereditary, and involved compulsory military service and military training throughout their lives among other things. Ironically, the Protestant Reformation had a great deal to do with mass education as they sought to reduce the influence of the Catholic clergy by teaching children to read the bible in their own native language. That's how mass literacy caught on.

Naturally, people who could read and write also learned to think more for themselves, and then could question whether kings, barrons and knights were really in their position by the grace and will of God. Even the modern notion of equality has its roots in equality before the eyes of God in the religious sense--and why the 20th Century rejection of Christianity is fraught with peril, because much of humanism is based on Christianity. Indeed much of humanism is just a plagiarism of Christianity and a huge heaping of religious iconoclasm. Yet, in many scientific disciplines, we more or less worship their prophets. When we refer to principles of electricity, we don't speak of current, frequency, flow, and so forth. We speak of Newtons, Watts, Volts, Amperes, Ohms, Joules, Hertz and so forth. Those are the new prophets or saints of the sciences--their surnames embodying the very concepts. Ironically, the average person doesn't know who they are anyway.

Local Localist wrote:Nothing, save an acceleration of societal progress, can come from everyone having an equal ability to flourish, and it is a great thing that people have been working towards this.

This is where I disagree with the Enlightenment. Not everybody has the equal ability to flourish. That should be carefully considered and distinguished from the

equal opportunity to flourish.

Rancid wrote:Interesting, so you are saying society is better of that we have the vast majority of people not really thinking for themselves and/or distracted by other things in life.

I would say that has always been the case.

Rancid wrote:More fundamentally it's replacement with the institution of reason/logic, which gives raise to science. Even if just a delusion I'd argue striving for reason/logic is better than religious indoctrination.

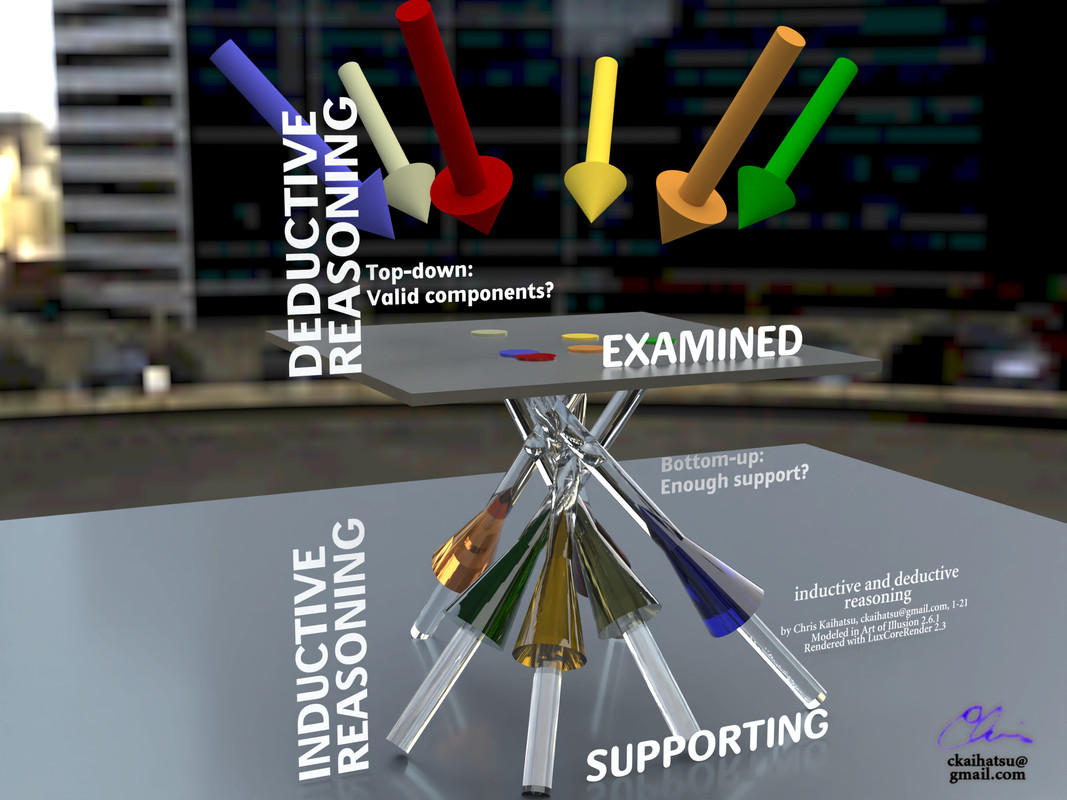

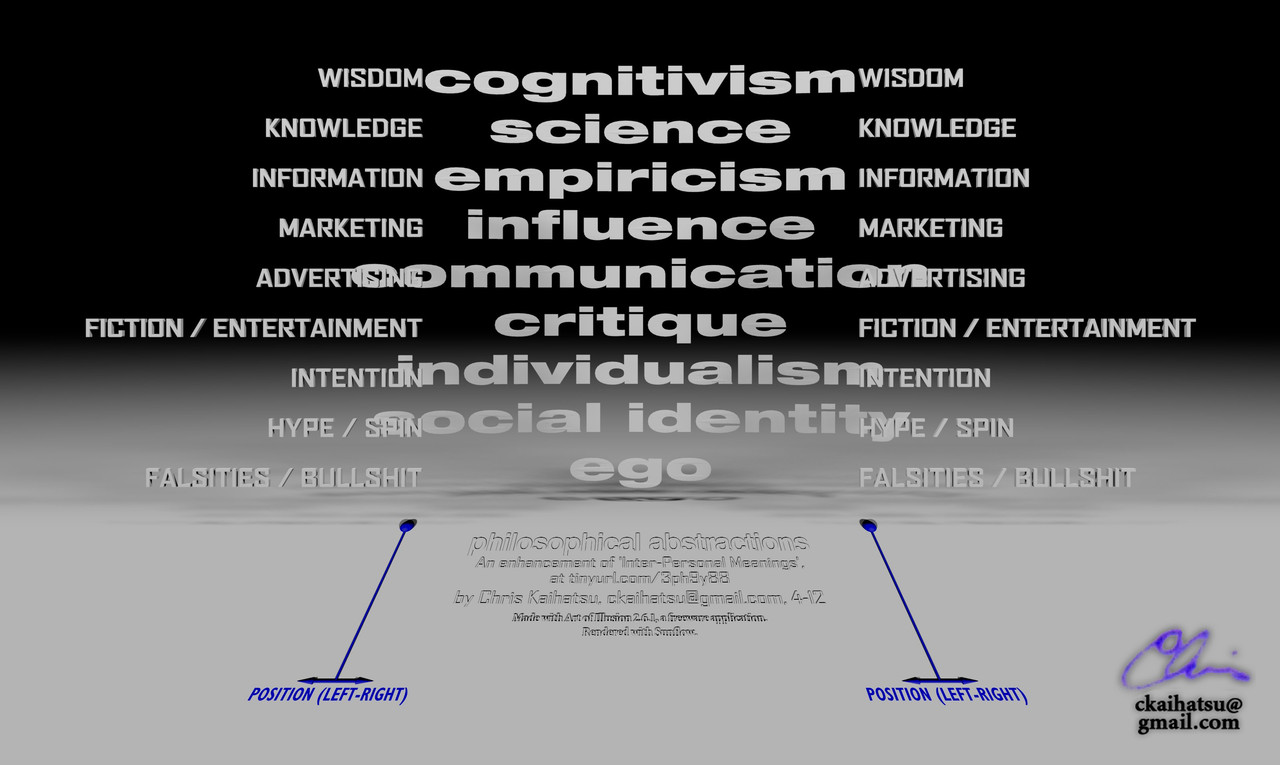

As we've been discussing across a number of threads, logic really provides internal self-consistency. It creates a foundation for the very introspection you spoke of earlier. For example, you can falsify a positive assertion if its contrapositive is false. It gets you closer to the truth--or more poignantly to more accurate descriptions of physical reality.

However, it does not do away with religious indoctrination as such and it doesn't undo the fact that we ultimately take everything on faith in the sense that even the sum of mathematics cannot be proven or disproven any more than the existence of God.

Rancid wrote:Then again, it has created the technology that prevents people from becoming enlightened.

I think it's overstating things to say that technology prevents people from becoming enlightened. I think its more reasonable to say that popular entertainment compels more of people's time than is warranted, and in some cases it is intended to prevent people from becoming "enlightened."

Atlantis wrote:There is no reason why human logic should produce a truthful representation of reality. Perhaps religious intuition results in a better representation of reality.

Logic by itself does not. It's logical interpretation of the observation (empiricism) of physical phenomena that does it. That's why science is useful.

Atlantis wrote:It's an artificial system set up by humans for our convenience.

No doubt that taxonomies change with new information or reinterpretation of existing information.

Atlantis wrote:We can use math, physics, etc. to build bridges and all kinds of useful things, but science doesn't give any answers to the ultimate questions.

Some people don't like the answers to questions, and rather that they not be asked at all.

Atlantis wrote:Ultimately, even advancing scientific knowledge requires intuition that is not too different from religious intuition. The understanding of matter in quantum physics is more akin to the Buddhist doctrine of emptiness than to classical physics.

Indeed. That's why I'm not as impressed with AI and machine learning because of the limitations of algorithms. However, I also concede that mass storage can now hold far more information than human brains, so we will likely learn of insights that only machines could reasonably compute.

Rancid wrote:Also, the mechanics of quantum physics is pretty well understood. I'm also not sure of anyone that claims science will answer the ultimate questions. Religion most certainly won't either.

This is why I contend that science--and the understanding of basic forces--remains incomplete. It's why I use metaphors like a roast beef sandwich with everything in the context of the Second Law of Thermodynamics. You just can't get to a sandwich with modern physics with reasonable levels of probability. It really requires something like intelligence as a first class force--or a force that is counter to the Second Law.

Rugoz wrote:It was observation that advanced quantum physics. I doubt anyone finds it intuitive when first confronted with it.

Nowadays there's apparently lots of unproductive theorizing akin to religion (i.e. string theory, according to some), but that's simply because it's not driven by observation.

That's because it's conjecture. There are some new algorithms for constructing conjectures now.

The Ramanujan Machine: Researchers have developed a 'conjecture generator' that creates mathematical conjecturesI don't think this stuff will be a panacea, but it will certainly lead to some breakthroughs.

Rich wrote:My knowledge of software development is greater than my knowledge of physics, but it seems to me we need individuals and groups to bash away on seemingly fruitless, even demented paths of exploration. Most will prove to be dead ends, but the few which do prove useful are of such benefit, that they outweigh the failures.

Yes, and that's why I think even discussing concepts like socialism is fruitless for moving humanity forward. As I'm in my 50s now, I definitely note the drawbacks of aging. Yet, it seems odd that we cannot do a better job of advancing health care, making it dramatically more productive and pushing the production possibilities forward. We know that we can use stem cells and grow things like a human ear auricle on a pigs back and so forth. Why should it not be possible for me to clone my liver, pancreas and kidneys at this point at a reasonable price so that I have spares if needed later? It's a shame that we lose people like Steve Jobs to pancreatic cancer, or that we have elderly people who have a chronic need for dialysis and yet we have no replacement kidneys banked when that is certainly within our reach at this point.

As a fellow computer head, I'm fascinated by genetics more than quantum physics, precisely because it is what we're all made of and it's biochemical, and it obviously incorporates intelligent and discrete behavior. That is an area that I think is a way forward for humanity, but the government doesn't get interested in it unless they can think of it in the context of an offensive or defensive weapons system.

Local Localist wrote:In my opinion, the great majority of people have never thought independently and critically, and I think we have evolved this way.

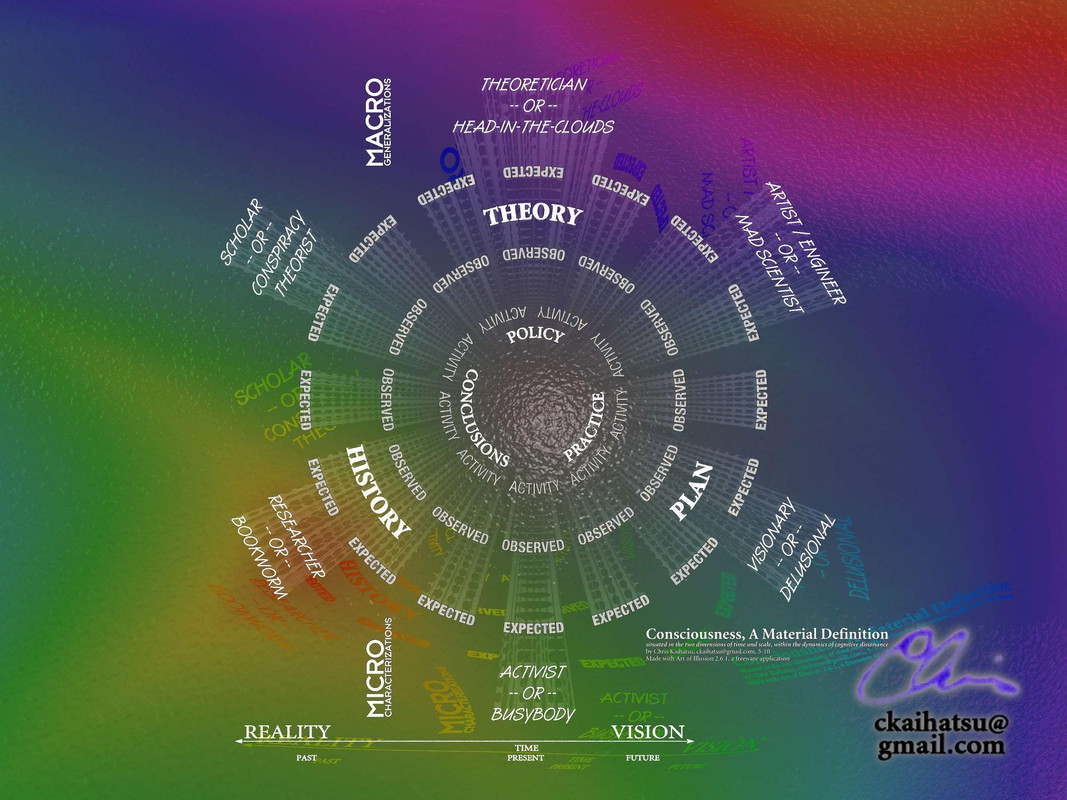

Yes. Humans are social animals. Learning something new necessarily means deviating from current beliefs. To the extent that groups are defined by maintaining existing beliefs, there is an almost aversion to acquiring new knowledge. This is why I said in Wellsy's post that my view is that we have to move past an "expert" based society, and towards one of problem solvers where the problem solver doesn't know the answer before addressing the issue.

Local Localist wrote:Hence, our social structures naturally take into account that only a minority of people will be visionary, so the majority will follow this minority.

And thus classes evolve naturally--or pecking orders as I chide Tainari88, because she can only see it as a hierarchy.

Rugoz wrote:Theorizing without the possiblity to empirically verify the theory is pointless.

Maybe to some extent, but what if you don't have an idea of how to empirically verify a theory? For example, Einstein didn't initially have a way of testing curved space time. Yet, they figured out an approach.

The True Story Behind How Albert Einstein Was Proved Right At A Solar Eclipse 100 Years Ago TodayOn May 29, 1919, astronomers from Britain traveled to Africa and Brazil to measure the exact position of stars in the Hyades star cluster in the constellation of Taurus. It was part of an ambitious, complicated and controversial attempt to see if, during an eclipse when the sky briefly darkened in the day, the stars appeared to be in the place where Isaac Newton’s long-accepted laws of motion predicted they would be, or whether they were where new-kid-on-the-block Einstein predicted. If the latter, science would have proof that the Sun (and, therefore, all stars and planets) curved space-time.

Think for example how long it took to realize a

Bose-Einstein condensate. Neither Bose nor Einstein lived to see it. It was just a theory that technology did not have the ability to produce. Bose died in 1974, but the BEC wasn't first created until 1995. Now they've done interesting experiments and note that light slows down in a BEC, but then reaccelerates to the speed of light as we know it as it leaves the BEC. Would you really contend that Bose and Einstein were wasting their time, because they did not live to be able to test their theory because of technological constraints of their time?

Wellsy wrote:I think this captures my attitude towards this attitude of the enlightenment.

Well, I think if we we're a bit more introspective about human nature, the idea that we COULD become less afraid would be easily understood as wrong as that is controlled by the limbic system--something enlightenment philosophers knew nothing about. Additionally, while physical sciences have gone to tremendous lengths to increase human survivability in the face of famine or disease, it has done very little to end violence among humans. Indeed it has given us weapons of mass destruction like nuclear weapons, and weapons of personal destruction like methamphetamine. Pandora's Box...

late wrote:It wasn't ancient history to them, and perfectly illustrated the abuses of religion, and the need for those impulses to be restrained.

Yes, but it wasn't religion itself that was rightly blamed for wars, as modern society demonstrated with the most horrifying bloodshed imaginable. Hitler, Stalin, Mao, and the French and British Empires were all quite rational. As I said before, Hitler did not violate the chemical weapons treaties by using them in battle; although, he used Zyklon-B against Jews and other people he considered undesirable. While the US didn't use chemical weapons either, it developed nuclear weapons. This adherence to the letter of treaties, but not at all to the spirit of them is an ongoing feature of our societies.

late wrote:Their communications became more secular.

Very little more in the 19th Century in my opinion. Read a history of General Patton or General MacArthur. Those men were secular in some senses, but in others they practically thought of themselves as gods. Most of the scientists were religious in some way--certainly not the atheists of today. Even mid-20th Century television shows would have nun shows or nuns as extras. It's really post-WWII after the '60s and '70s that you see none of the old nuns being replaced, church bells tolling the hour of the day and so forth. The latter being a product of atheists suing for noise pollution and so forth. Yet, if I'm in Dubai with my work colleagues, a request of "Can you get this done this week?" is ultimately met with "Insha'Allah" and it is totally normal. Yet, in the States if I answered my boss with "If God wills it," I'd probably be on a corrective action plan.

late wrote:But the decline and fall of the political power of religion is a big part of my thinking.

Indeed it is, but of traditional religion. Not modern variants like scientism, and so forth. One thing that imaging has taught us is that when people are having what they believe are religious experiences, a certain part of their brain is activated. Imaging shows that clearly. It seems we are wired for religion of some kind. The flip side of that is that the irreligious probably rarely use that part of their brain. If that part of our brain is necessary for the next wave of scientific discoveries, certainly atheists will underperform.

"We have put together the most extensive and inclusive voter fraud organization in the history of American politics."

-- Joe Biden