- 31 Jan 2017 07:27

#14770137

Zach Vertin wrote:Punishing Sudan Is Not a Strategy

But Engaging a Bad Regime Could Make It Better

On a bitterly cold Washington morning eight years ago, a newly sworn-in president took to the inaugural podium and leveled a challenge to the world’s worst governments. “Know that you are on the wrong side of history,” a resolute Barack Obama said, “but that we will extend a hand if you are willing to unclench your fist.” In the years that followed, Obama followed through on his pledge by initiating strategic openings to both Iran and Cuba. In the final weeks of his presidency, he likewise announced a shift in policy on Sudan—another country with which the United States has long had hostile relations—including the easing of sanctions. He was right to do so, and now President Donald Trump should carry forward what his predecessor started.

Although the move came conspicuously late in Obama’s tenure, it is in fact the culmination of an initiative that began nearly two years ago through a series of bilateral talks. The initiative marked a recognition that Washington stood a better chance to achieve its goals in Sudan through a smarter, more flexible diplomacy—one that combines both pressure and engagement.

A corrupt and brutal regime has held sway in Sudan for a quarter century. It concentrated power in its capital city while marginalizing and violently suppressing citizens in outlying regions—Darfur, the Nuba Mountains, and Southern Sudan. For two decades, Washington pursued a policy dominated by economic sanctions, pressure, and isolation. The goal was to force Sudan’s regime to change, and, if that failed, to force regime change. And for two decades, that policy failed: Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir’s government has not undertaken the domestic reforms necessary to create a peaceful and more inclusive system of governance, nor has it been dislodged.

Washington’s punitive approach was lacking in two ways. First, pressure works best when it is applied in conjunction with a full range of global actors. And second, it must be complemented by a strategy to engage a government toward desired objectives. In Sudan, for too long, the United States did neither.

In response to the United States’ imposition of sanctions in the 1990s, Khartoum simply turned east, developing an economic relationship with an emergent China. It supplemented this partnership with a transactional foreign policy, dealing tactically with states in Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa. It traded favors for political and financial lifelines, and it cracked down on dissent at home.

Meanwhile, U.S. sanctions hurt average Sudanese citizens, many of whom are not regime supporters. Hospitals lacked critical supplies, consumers faced high price tags on imported goods, workers struggled to send remittances to families in need, and businesses struggled to stay afloat. At the same time, the regime was able to deflect responsibility by blaming the United States for its economic woes.

Political pressure from Washington fared little better in changing the regime’s awful behavior at home. When the United States chose, instead, to engage Sudan’s government in 2005 and 2010, wielding both carrots and sticks, some progress was achieved. But otherwise, frustrated by Khartoum’s intransigence, Washington too often chose demonstrations of contempt over nuanced engagement.

In 2015, U.S. diplomats began pursuing a different strategy. After several rounds of talks with Sudanese officials, they presented a road map for engagement. Khartoum would stop its military offensives in marginalized regions, allow humanitarian aid to reach people in need, cooperate on counterterrorism efforts, and refrain from meddling in the ongoing conflict in South Sudan, which became independent in 2011 with U.S. backing. (Contrary to some reactions to Obama’s announcement, neither counterterrorism nor Middle Eastern geopolitics were the driving force behind the U.S. policy shift.)

In exchange for progress on these benchmarks, Washington would begin easing sanctions, lifting its trade embargo, and offering other modest incentives. These first steps would credibly demonstrate to Sudan that it, too, could come in from the cold. But the deal would also be structured to leave Obama’s successor with plenty of additional tools and leverage to carry the process forward. (In addition to a built-in progress review in 2017, the appointment of an ambassador, the lifting of designations on sanctioned individuals, and the unblocking of multilateral financing and debt relief are among the things Khartoum still desires.)

Sudan agreed to the road map and has since upheld its conditions, as measured during a dozen joint progress reviews. Although important, its adherence to the benchmarks is not a signal that all is well in Sudan. The repressive regime remains a long way from fully unclenching its fist. In addition to articulating next steps—further relief for further progress—Trump’s administration should reiterate that punitive measures can be snapped back in place if Khartoum defaults on its commitments.

As with the cautious openings to both Cuba and Iran, engaging Sudan does not amount to appeasement of a bad government; it is a strategic move designed to promote long-term change. And it, too, is intended to strengthen moderates and undermine the hard-liners who have held sway within the regime as long as the United States has been hostile to it. Credible incentives afford moderates the space to argue for further reforms and gradual reintegration into the global community.

On that January morning eight years ago, Obama also warned leaders who sought to “blame their society’s ills on the West” of how their constituencies would weigh their actions. “Know that your people will judge you on what you can build, not what you destroy,” he said. Obama’s easing of sanctions will also snatch from the Sudanese regime its favorite propaganda tool, using the United States as a scapegoat, and put the onus for oppressive misrule squarely on Khartoum’s own shoulders.

Gradual change is not easy. But longtime proponents of forceful regime change in Sudan have thought little about how it would happen, and even less about potential consequences for ordinary citizens—questions for which Iraq and Libya provide important lessons.

Critics of Obama’s announcement will be vocal. They have legitimate concerns, given Khartoum’s record of duplicitous behavior. But an unflinching opposition to any kind of engagement isn’t a strategy. It is time to acknowledge that pressure alone has achieved little. Supporting the Sudanese people remains the primary objective, and although punishing a dreadful government may be morally satisfying, we must instead be guided by results.

Foreign Affairs

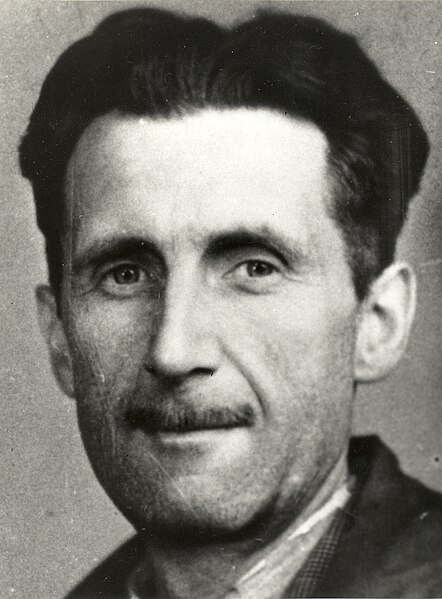

We have now sunk to a depth at which restatement of the obvious is the first duty of intelligent men -George Orwell

- By Tainari88

- By Tainari88