Additionally, these problems were known about even while the F-35 was being designed, sadly. See here:

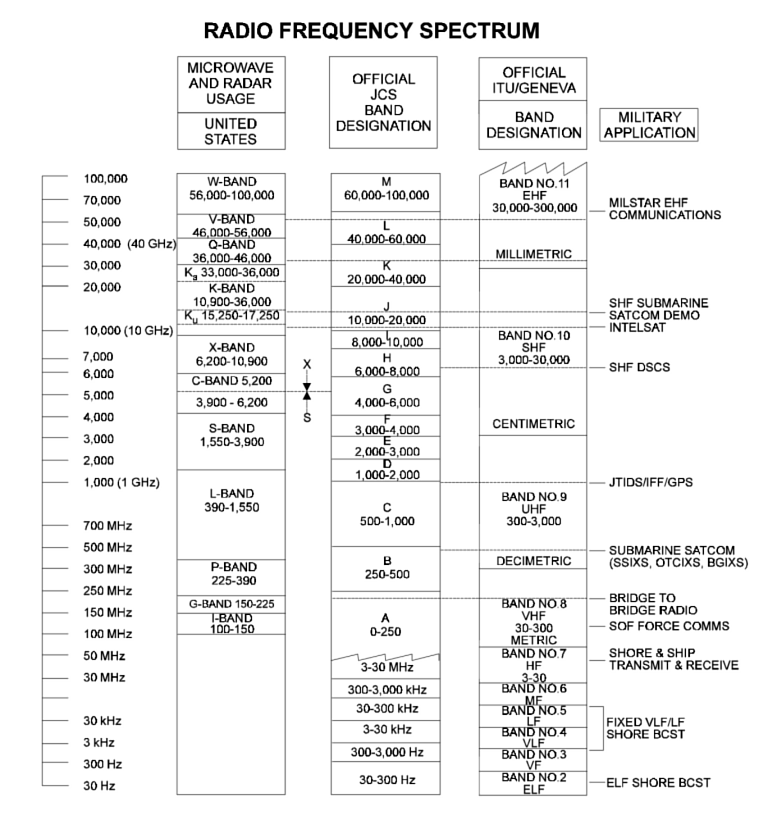

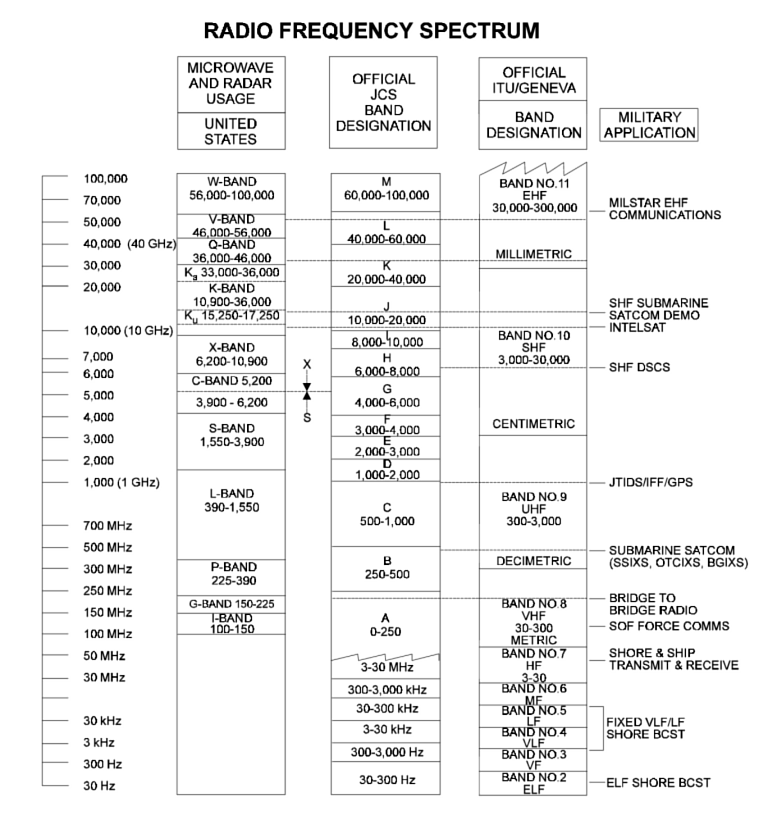

Air Power Australia, 'Assessing Joint Strike Fighter Defence Penetration Capabilities', 07 Jan 2009 (emphasis added) wrote:[...] The second major departure from established stealth conventions is that the Joint Strike Fighter is designed to perform in the X-band, and upper portions of the S-band, with little effort expended in optimizing for the lower L-band, UHF-band and VHF-band. This design strategy is consistent with defeating mobile battlefield short range point defence SAM and AAA systems such as the SA-8 Gecko, SA-9 Gaskin, Chapparel, Crotale, Roland, SA-15 Gauntlet, SA-19 Grison and SA-22 “Greyhound”, where limited radar antenna size forces all acquisition and engagement functions into the X-band and upper S-band. Joint Strike Fighter literature refers to this optimization in terms of “breaking the kill chain”, the intent being to deny the effective use of X-band engagement radars and X/Ku-Band missile seekers, but not acquisition radars in lower bands.

Such SAM systems are the category of “residual” threat which a battlefield interdiction aircraft will encounter once the F-22A force has “sanitized” an area by destroying the long range search/acquisition radars and area defence SAM batteries. With limited range and coverage footprint, but high mobility and autonomous capability, battlefield short range point defence SAM and AAA systems can “pop-up” from hidden locations and ambush interdiction aircraft at medium to low altitudes. Significantly, in a “sanitized” environment such air defence weapons are operating without external support from other sensors or the top cover provided by long range area defence SAMs such as the SA-12/23, SA-20 and SA-21.

The engine nozzle presents a good case study of the band dependency of stealth performance in the Joint Strike Fighter design. In the upper X-band and Ku-band, the individual nozzle segments present as flat panels with a serrated trailing edge. The result will be a circular pattern of narrow reflecting lobes which will produce mostly good effect in these bands. However, in the lower bands this arrangement will rapidly degrade in behaviour to that of a truncated conical shape, which is a strong specular reflector. The resulting external shape related signature will be much the same as a conventional exhaust nozzle on a non-stealthy fighter, with an outer skin contribution and rim contribution. While the interior of the nozzle will be coated with broadband lossy materials and a tailpipe blocker used to obscure the turbine face, the signature of the nozzle exterior below the X-band cannot qualify as “stealthy”.

[...]

The aircraft performs best in the X-band, and Ku-band, with performance declining through the S-band with increasing wavelength. In the L-band the axisymmetric nozzle design no longer produces useful effect, and the length of the inlet edges sits in resonant mode scattering rather than clean optical scattering, degrading performance. In the VHF band (~2 metres) Joint Strike Fighter airframe shaping has become largely ineffective.

The aircraft will have a credible ability to defeat S-band search/acquisition radars, X-band engagement radars and X/Ku/K/Ka-band missile seekers only in the narrow ±14.5° angular sector under the nose. As the angle relative to the threat radars increases, the unfortunate lower fuselage shaping features will produce an increasingly strong effect with a cluster of “flare spot” peaks around 90° where the longitudinal panel and door edge joins produce effect.

In the narrow ±14.5° angular sector under the tail, the design will produce best effect against X/Ku/K/Ka-band missile seekers, but less useful effect against X-band engagement radars due to their higher power-aperture performance. At S-band the nozzle exterior signature will become increasingly prominent, leading to loss of effect in the vicinity of the L-band.

It is clear that these design choices were intentional and no accident. By confining proper stealth shaping technique only to the forward fuselage and inlet geometry, the designers avoided incurring the development, and to a lesser extent, the associated manufacturing costs of a fully stealthy design, with the YF-23A and F-22A presenting good comparisons.

This is an acceptable optimization if the intent is only to defeat an isolated individual low power aperture pop-up short/medium range mobile battlefield air defence system in the category of the SA-6 Gainful, SA-8 Gecko, SA-9 Gaskin, Chapparel, Crotale, Roland, SA-11 Gadfly, SA-15 Gauntlet, SA-19 Grison or SA-22 “Greyhound”. It is a completely unsuitable optimization for a wide range of other threat types which are in service, and the associated characteristic engagement geometries. It is also a problematic optimisation where short/medium range battlefield air defence systems are deployed in a coordinated manner.

The most generous description of the stealth design used in the Joint Strike Fighter is that it is 25% VLO, in the nose sector, 25% LO in the tail sector, and 50% “reduced observable” in the beam sectors, with a strong threat operating frequency and angular aspect dependency in stealth performance. It is clearly not a stealth design in the same sense as the F-117A Nighthawk, B-2A Spirit, YF-23A and F-22A Raptor, and to label it a “VLO design” is at best a “quarter-truth”, quite indifferent to the physical realities of the design and the threat systems it will need to defeat in future conflicts.

[...]

The pragmatic reality is that the threat environments which were used to define the stealth capability of what is now the Joint Strike Fighter are artifacts of history, since then re-equipped predominantly with longer ranging SAMs and more powerful radars. There has also been over a decade of technological evolution in Russian radar and missiles since 1997. In the simplest of terms, all of the basic technological assumptions used to define the stealth capabilities of the Joint Strike Fighter are no longer true.

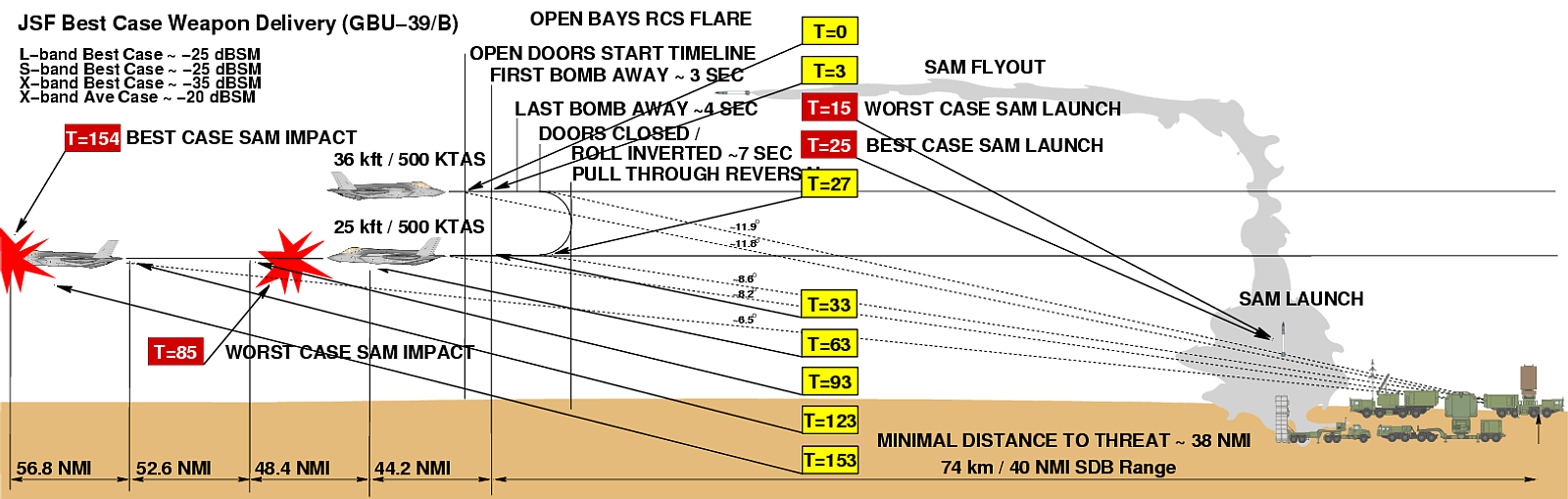

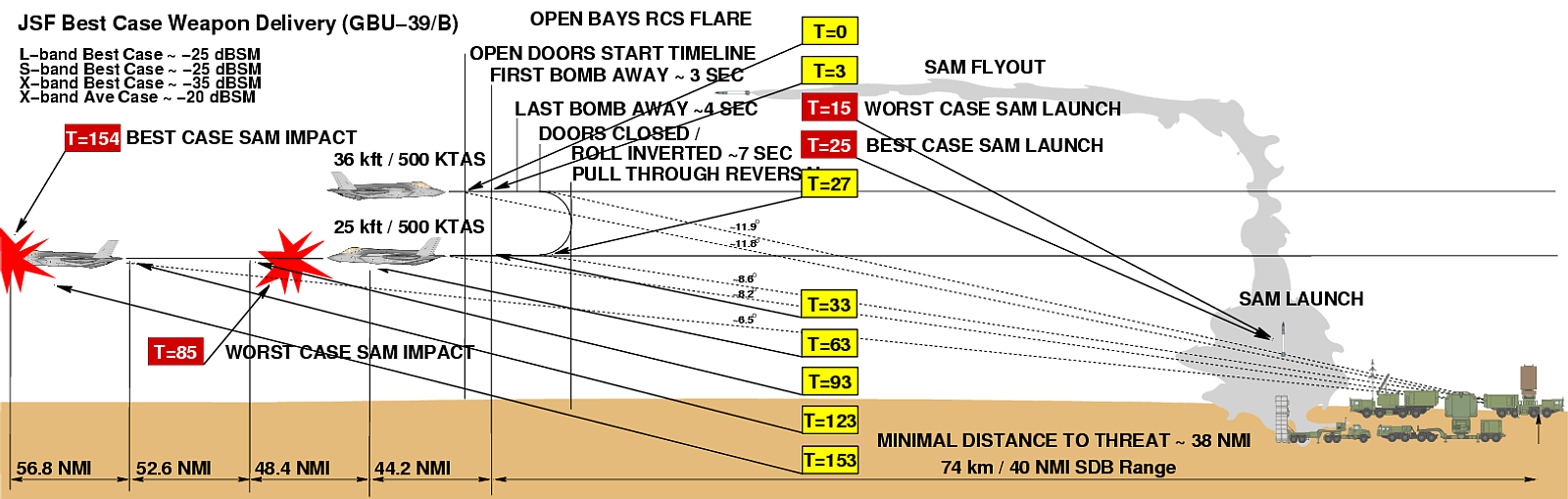

While potential threat nations replaced medium range SAMs with long range SAMs, and radars and SAMs evolved from analogue to digital, the Joint Strike Fighter’s design evolved in the opposite direction, with its stealth shaping progressively degraded in key areas. Diagram 6 illustrates a best case (for the Joint Strike Fighter) engagement using contemporary (and some legacy) long range SAM technology.

This diagram depicts the best case engagement geometry and timelines for an attack using the Small Diameter Bomb against a target colocated with a long range SAM site, or the SAM battery itself. Level turn escape manoeuvres do not minimise the exposure time of the F-35 and in addition present a larger depression angle to the threat. The single best escape manoeuvre after bomb release is to roll inverted, and pull through. Airspeed is constrained to 500 KTAS to minimise nozzle RCS. The difficulty is that even for the best case and worst case SAM parameters for SA-10, SA-12, SA-20 and SA-21 the missile battery gains a robust firing opportunity. Within the ranges of interest the F-35 from this aspect can still be tracked for a missile shot by the 59N6E, 67N6E, 96L6E, 36D6, 64N6E2, 5Zh66 and 1L119 3D acquisition radars and the 9S19, 30N6E1/E2 and 92N6E engagement radars. At this range the aircraft can be tracked by the Vostok E, JY-27, 1L13, 5N84AE and P-18M 2D acquisition radars. A large fraction of these radars post date the initial requirements definition for the Joint Strike Fighter. In the contemporary IADS environment it is therefore abundantly clear that the Joint Strike Fighter cannot survive by stealth alone, as the threat radar technology has evolved considerably over the last decade.

None of these issues arise with the F-22A Raptor as it can release the GBU-39/B from a much greater range, and it can egress almost twice as fast, while it can considerably better aft sector and lower fuselage RCS performance.

As the Joint Strike Fighter evolved through the SDD program, the shaping of the lower fuselage departed strongly from the X-35 Dem/Val configuration, increasing the radar signature from the beam/side aspect. As a result the aircraft’s susceptible angular extent increased dramatically, leaving only the nose sector with a credible stealth capability.

The inevitable conclusion at this point in time is that for the Joint Strike Fighter to become survivable against anything other than trivial isolated short/medium range SAM systems, it will require fundamental changes to its avionic and antenna aperture architecture, to incorporate a Digital RF Memory based active jammer with the angular coverage and emitted power levels to overcome the signature problems introduced by the SDD program.

The problem with pursuing this necessary design change is that it will be expensive in development costs, weight, power and cooling, even if off the shelf jammer technology is employed. This is due to the need to provide wideband antenna apertures for the jammer which do not compromise or degrade what little remaining stealth capability is left in the SDD Joint Strike Fighter design. While the wideband AESA technology being developed for the Navy’s Next Generation Jammer effort might be exploited, unlike the large F-22A which has airframe provisions for sidelooking AESA arrays, the Joint Strike Fighter design would require structural changes to make space available.

The options of carrying external jammer pods on pylons, or jammers embedded in pylons, are technically simple but would further exacerbate the extant problems with stealth performance.

Why the Joint Strike Fighter Program Office and manufacturer opted to disregard the well proven stealth shaping techniques used in the F-117A, B-2A, A-12A, YF-23A and F-22A remains an open question. The most plausible explanation is that the combined pressures of the “Cost As an Independent Variable” philosophy, and internal volumetric demands, forced the designers to expand lower fuselage cavities, the main undercarriage bays and weapon bays, and the only way this could be accomplished without major structural changes was by altering the lower fuselage shape, at the expense of beam/side aspect stealth performance.

What is clear is that the introduction of the poorly shaped SDD lower fuselage design was not accompanied by the necessary analytical reassessment of the aircraft’s resulting survivability degradation and what measures would be required to overcome the reduction in stealth performance so produced.

The failure in technological strategy was thus reinforced by a failure in program engineering management.

[...]

The Russian and Chinese technological strategy for dealing with penetrating all aspect stealth aircraft has been to develop a new generation of VHF band radars, including multistatic forward scattering radars. These will reduce opportunities for undetected penetration, especially by fighter sized aircraft, as the VHF radars defeat shaping measures and materials designed for S-band and X-band threats.

The US Air Force technological strategy for dealing with this counter-strategy is the use of the F-22A Raptor, armed with the GBU-39/B Small Diameter Bomb, for lethal suppression of such radars. A pair of F-22As, armed with sixteen SDBs in total, can overwhelm the point defence SAM systems defending critical search radars.

The inferior “single aspect stealth” capability of the Joint Strike Fighter denies it the option of penetrating a modern IADS SAM belt. The depth of the IADS simply makes it geometrically impossible to find a path between search radars where the combination of distance and relative aspect would allow it to penetrate unseen. This is exacerbated by the increasing availability of modern digital VHF, UHF and L-band search radars, especially radars with 3D capability and the accuracy to guide long range area defence SAMs.

The limited 40 NMI standoff range and time of flight of the GBU-39/B SDB glidebomb denies the Joint Strike Fighter the use of the lethal suppression strategy flown by the F-22A. Most missile batteries will have “scooted” away from the bombs’ aimpoints before they arrive. Indeed, the range from which the Joint Strike Fighter would need to release the SDB would in many IADS geometries leave it exposed to long range SAM shots, which it is ill equipped to handle.

The result of increasing IADS capabilities and the degradation of the Joint Strike Fighter’s stealth design through the SDD leaves it with only one tactical option for penetrating an IADS environment.

That option could be best labelled as “shooting a path through defences”, which is essentially the “conventional” model pioneered and perfected during the Vietnam conflict and incrementally improved since then. In this model a strike package intended to penetrate an IADS will be escorted by aircraft armed with anti-radiation missiles such as the HARM family of weapons. These are launched in large numbers to destroy threat radars which continue to emit, and force others to shut down for fear of attack.

This strategy in its basic form is now in its twilight years, and basically only useful against legacy IADS equipped with Cold War era weapons. This is a result of two basic changes in IADS operating doctrine and supporting technology. The first of these is the adoption of active emitting decoys which will seduce some fraction, if not ideally all of the anti-radiation missiles launched. The second of these is the modern practice of defending search and engagement radars with “counter-PGM” capable short range point defence missiles, such as the SA-15, SA-19, SA-22 and the 9M96E missiles in the SA-21 system. Such missiles are intended to shoot down inbound anti-radiation missiles – or glidebombs.

As a result, this strategy will require heavy saturation attacks as a large proportion of the anti-radiation missiles launched will be decoyed or soaked up by point defence SAM defensive fire. A strike package intending to penetrate an area defended by a single battery of SA-20/21, supported by the SA-15, SA-19, SA-22 and/or the 9M96E missiles in the SA-21 system, would need to deliver of the order of 32 or more anti-radiation missiles to exhaust the typical point defence SAM ready round loadouts.

In 2002 the Threshold Weapons package for the SDD Joint Strike Fighter included up to four externally carried AGM-88 HARM anti-radiation missiles, this presumably including planned derivatives such as the multimode seeker equipped AGM-88E AARGM. A year later the HARM vanished from the SDD weapons package.

This has important implications, assuming that the HARM or a follow-on weapon can be successfully cleared from the long and forward displaced pylons used by the Joint Strike Fighter. The first of these is that the capability to use this IADS penetration technique will not be available until the 2020 timeframe, post SDD.

More importantly, the degradation in the stealth capability of the Joint Strike Fighter through the SDD program is forcing the Joint Strike Fighter into the use of a defence penetration strategy no different to that used by legacy aircraft, which is inherently expensive in expended munitions and in the number of sorties required to achieve a given effect. There is no economic advantage to be found in this game by using a Joint Strike Fighter instead of a HARM shooting legacy type such as the F-16, or F/A-18 (with its aeroelastic limitations) or, better still, the very capable HARM shooting F-111.

One of the principal reasons which justifies the additional design and maintenance expenditures on stealth aircraft is that significant economies can be produced by using all aspect stealthy penetration techniques – only the aircraft carrying bombs to strike targets need to be deployed, and a minimum of supporting aircraft are then necessary, with munitions expenditures limited to the bombs required to do the job. The SDD Joint Strike Fighter with its impaired stealth cannot use this strategy, and the operational economics are thus degraded to those of legacy aircraft, but still incurring nearly all of the cost burdens of a proper all aspect stealth design.

In technological strategy terms the Joint Strike Fighter design is thus “pennywise and pound foolish” in the sense that the design is carrying most of the cost burden of an all aspect stealth aircraft, but it is not stealthy enough to exploit the benefits which are inherent in a good stealth design, and thus incurs most of the operational economic burdens of a non-stealthy legacy aircraft.

So in other words, the F-35 is pretty horrible.

This is the only 'upside':

Air Power Australia, 'Russian / PLA Low Band Surveillance Radars', Apr 2012 (emphasis added) wrote:[...] Low band radars are not a panacea for the defeat of VLO (Very Low Observable) aircraft. Their angular accuracy has been until recently poor, and the required antenna size results in ungainly systems which are usually slow to deploy and stow, even if designed from the outset for mobility. The size and high power emissions of these radars, in types with limited mobility, makes them much easier to detect and destroy than typical mobile systems operating in the decimetric and centimetric bands, which can relocate rapidly after a missile shot.

Despite these drawbacks, the older Russian low band radars still provide a valuable early warning capability, and enable cueing of other sensors and platforms. In an IADS context, a 55Zh6 Nebo, 1L13 Nebo SV, Nebo SVU or 5N84 Oborona would be used to cue the high power aperture X-band 30N6E Flap Lid/92N2E Tomb Stone series and 9S32M Grill Pan series engagement radars in the S-300PMU, S-400/S-400M and S-300VM systems to a small acquisition box in which the VLO aircraft can be found. This allows significantly more RF power to be focussed into a small volume of space, increasing the probability of detection. Some newer radars such as the Nebo SVU , Gamma DE and Protivnik GE are accurate enough to direct a missile shot, using the engagement radar primarily as a midcourse command/datalink channel to the missile.

Where fighters with high power aperture X-band radars are available, such as Irbis-E or Zhuk ASE equipped Su-30/35 Flanker E/G/H variants, a low band radar can provide GCI vectors to position the fighter near enough for acquisition of the target, if need be with other sensors such as an IR Search and Track set.

In practical terms one of the key advantages of VLO aircraft, surprise, is largely denied by the use of such systems. The VLO capability is still enormously valuable in terms of degrading or defeating most engagement radars and missile seekers, but the defender regains access to the early phases of the engagement cycle otherwise also defeated by VLO capability.

The US Air Force is expected to use the F-22A Raptor armed with the glide wing equipped GBU-39/B SDB to destroy a defender's low band systems in the opening minutes of an engagement, relying on the standoff range of the weapon and speed/altitude of the fighter to deny engagement opportunities by defending IADS elements being cued by the low band radars. Other fighters do not have these capabilities and become exposed to defending IADS elements.

The notion that Russian low band radars are artifacts of the Cold War with little combat value is foolish, as current production models are typically 'digitised' through most of the signal and data processing, and display components, and many now use solid state transmitters. At least two designs are AESAs (active phased array). Russian manufacturers have thus followed much the same trend as Western manufacturers, enhancing Cold War era systems designs with digital processing. More than often modern Digital Moving Target Indicator (DMTI) or digital pulse Doppler techniques are employed, some types also using Space Time Adaptive Processing (STAP), exploiting the high performance of COTS computing technology, readily available in the open market and easy to ruggedise for a semi-mobile application of this kind.

Russian industry is very actively marketing digital upgrades to the P-18 Spoon Rest, and new production digital 55Zh6 Nebo UE / Tall Rack and Nebo SVU VHF radars, specifically as a "Counter-Stealth" capability.

The net effect of this seems to be that the F-35 becomes a kind of lame duck whenever it is used against a

non-backwater opponent and the F-22A is

not present. However, only the US Air Force operates the F-22A, although lots of countries are going to be operating the F-35. So you see the problem here.

One part incompetence, another part dependency-inducing. The net effect has been that the F-35 is a massive waste of time and money. But every time I criticise this plane, people respond by saying some nonsense like, "nyah, nyah, you just don't like it because it was designed by Lockheed Martin", as if anyone is really that petty.